International mining firm Glencore’s local joint venture Katanga Mining has stopped exports – but not production – of cobalt from its Kamoto mine in the far south of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), citing concerns about excessive radioactivity. It has proposed to first set up a machine to remove radioactivity, but reports suggest that this would not be operational until Q219. The government in Kinshasa has protested this move as it claims it was not consulted and state-owned miner Gecamines – which owns 25.0% of the mine – argues that it had no part in the decision.

This would also impact our currency outlook, as at present we forecast the Congolese franc to remain broadly stable due to strengthening metals exports. If exports were significantly affected, given that the central bank has foreign reserves equivalent to only five weeks of import cover as of September 2018, then the currency may have fewer means to resist depreciatory pressure than we currently expect.

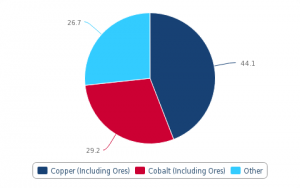

Cobalt Export Decline Would Have Significant Impact

Implications: The Kamoto mine is a major source of cobalt and if it does indeed stop exports until the end of Q219, this would have an impact on the DRC’s external position. Though production would not stop, and presumably the cobalt would be exported from Q319 onwards, the impact on the current account balance in the next six months could be major. Indeed, cobalt and cobalt ores made up around 29.1% of Congolese goods exports in 2017 and the withholding of cobalt exports over the next several quarters would undoubtedly impact on the pace at which the DRC’s current account deficit narrows.

The fact that Katanga Mining unilaterally ceased exports without consulting either the official environmental regulator or the government-owned mining stakeholder also suggests that the government’s control over mining companies is weak. It also suggests that relations between the state and the mining giant are poor.

This would also have some fiscal implications, as the government revised its mining charter in 2018 with much stricter provisions including higher taxes and the ability to revise contracts much more easily than hitherto. The fact that the government was unable to prevent a unilateral action at a mine it part-owns suggests that its ability to properly assess and collect mining revenues and to enforce regulations is also limited. Indeed, the government has already found itself in a quandary in mid-2018 after incorrectly taxing Glencore’s Kibali mine, leading to the mine being exempted from VAT as compensation. This suggests that the actual revenue growth from higher mining taxes may be somewhat limited, meaning that the fiscal position may worsen by slightly more than we currently expect in 2019.

Finally, this suggests that the government’s ability to influence events in some of its more remote provinces such as Katanga is limited. This suggests that if – as we expect – the December 23 election sets off a major outbreak of unrest in urban areas in the west, then the government’s control over Katanga may weaken even more.

What Next: We will wait to see if Glencore does meet with the government or whether the suspension of exports remains in place and if it remains as such for as long as end-Q219. If exports are indeed suspended for six months then we are likely to revise our current account deficit and exchange rate forecasts. If the halt in exports is overturned or reduced to a limited time span, then it will not be necessary to change our forecasts.

Source: BMI Research